|

Interviews:The first entitled From Coronation Street

to the Kingdom of Darkness by Andrew Hedgecock in The 3rd

Alternative. The second was an interview with an internet-based magazine. |

|

|

From Coronation Street to the Kingdom of Darkness.

Trevor Hoyle interviewed by Andrew Hedgecock in The 3rd Alternative, 2003.

Britain in the mid-1980s - the era of Thatcherism triumphant. She who wasn't for turning, having seen off the 'enemy within' in the form of the National Union of Mineworkers, surveyed an empire built on cant about 'modernisation', 'enterprise', 'freedom' and 'choice'.

Communities were crumbling, homelessness spiralling, working conditions deteriorating, the welfare state unravelling and, forgive the pun, arms sales rocketing. There was, we were told, 'no such thing as society'.

There were winners in this vast experiment in social engineering. For them, greed was good: anaesthetised by the soma-cocktail of celebrity, affordable overseas holidays and lifestyle aspirations, they managed to avert their eyes from victims of the free market and state-sponsored violence. And the losers? They could always resort to the officially sanctioned means of escape from the tidal wave of unemployment and insecurity - Norman Tebbit's hand-me-down pushbike.

The legacy of Thatcher's 'radical philosophy' is still with us, but 20 years ago its effects were fresh and frightening. Strangely, the immediate response from British writers and filmmakers was, in the main, meagre and grievously uncompelling. It was as if the seismic scale of these economic, social and psychological shifts left them unable to steer the tricky channel between the Scylla of trivialisation and the Charybdis of sententious didacticism.

Consider some of the most memorable work from this period. Alan Bleasdale's Boys from the Blackstuff, captured the desperation of the victims, but had little to say about the pernicious psychology that produced it. Then there was the blanket-bombing misanthropy of Lindsay Anderson's Britannia Hospital and the fainthearted, shop-worn satire of Ian McEwan's A Child in Time. But there was Trevor Hoyle's Vail too.

A

blend of science fiction, surrealist vision and classical picaresque, Vail

is a grim, and occasionally hilarious, journey into the psyche of a nation

seriously at odds with itself. It follows the fortunes of Jack Vail through

a totalitarian England, from the wrong (northern) side of 'the wire', a dumping

ground for toxic waste and people who have lasted beyond their economic sell-by

date patrolled by helicopter gunships, to a celebrity obsessed London drenched

in pornography and conspicuous wealth.

A

blend of science fiction, surrealist vision and classical picaresque, Vail

is a grim, and occasionally hilarious, journey into the psyche of a nation

seriously at odds with itself. It follows the fortunes of Jack Vail through

a totalitarian England, from the wrong (northern) side of 'the wire', a dumping

ground for toxic waste and people who have lasted beyond their economic sell-by

date patrolled by helicopter gunships, to a celebrity obsessed London drenched

in pornography and conspicuous wealth.

Vail is a howl of pain and a volley of mocking laughter: relentlessly angry but coolly analytical, it's a deeply disturbing portrait of the dispossessed and their tormentors that resists the urge to preach. I came across a copy in Amersham library in 1986, on an afternoon off from a job where I was nicely cushioned from the excesses Hoyle was writing about. I didn't need a novel to tell me what was going on - people I'd grown up with were experiencing the flipside of Mrs Hatchet's vision. And of course I knew the extent to which those of us who'd staggered on to the comfortable side of 'the wire' were complicit in the suffering of those who hadn't been able to. But after devouring Vail in a single sitting, I somehow knew those things a little more deeply. Trevor Hoyle is a modest man whose writing never veers into didacticism, so he'll be astonished to learn that Vail was the catalyst for a period of frenetic political activism for at least one reader.

It's a book I keep returning to - some of the name-checked celebrities may have faded or dropped off the perch, but its exploration of the dark side of the English psyche has lost none of its relevance in the intervening years. So when I get the chance to talk to Trevor Hoyle for TTA, Vail is the obvious starting point - after we've discussed the horrors of being a visiting supporter at Mansfield Town, struggled to come to a firm conclusion about Michel Houellebecq and shared memories of self-advancing pit props (Hoyle wrote copy for the manufacturers and my father was a mining engineer).

"Vail was a very personal reaction to Thatcherism - I was just appalled by the way, in my view, she was tearing the country down piece by piece. It was a direct and furious response to the most evil and pernicious cult of saying 'fuck you' to large segments of the population and effectively wrecking this country for good. I wrote the book in 1983. It was due to be published by John Calder in 1985 but I asked John - as a special favour - if he could bring it out in 1984, to capture the significant symbolism of that year, and he did. It probably didn't matter to the reader, but it was important to me that it came out in that year."

The enduring impact of the book is due, at least in part, to Hoyle's decision to eschew the gritty realist mode of storytelling traditionally associated with this kind of material for a fusion of apocalyptic fantasy, future thriller and dreamlike black comedy. In the hands of a less accomplished storyteller, narrative and theme could have been muffled by this medley of moods and forms. But Hoyle's uncanny knack for finding precisely the right voice is a defining characteristic of his novels.

"The style is fairly clean and spare because it reflects my very naked response. When I look back upon the books I've written, some I'm less happy with, others more. Vail works as well as I could make it work. Books always fall short of a writer's expectations: you always set out to write the perfect book and, of course, you never can. But Vail comes very close to what I set out to do in terms of both style and content."

The sullen watchful army.

Hoyle is refreshingly open about his attitude to work. Vail may have been a source of inspiration for me, but its author has no time for writers who sit around waiting for a visitation of the muse.

Books like Vail, the complex and deceptive thriller Blind Needle and the experimental, stylistically dense Man Who Travelled on Motorways put Hoyle on the same list as Samuel Becket, William Burroughs and Alain Robbe-Grillet. And his radio plays Gigo and Randle's Scandals have won critical acclaim and awards. But this is a writer who has tackled Blake's 7 tie-in novels with the same commitment and sense of craft - if not the same relish - as the work that has brought him an enthusiastic audience that includes fellow writers Chris Petit and Nick Royle. His approach is exemplified by our discussion of the excessive attention granted to the 'big beasts' of literary fiction.

"Like you I think Amis, McEwan and company are very overrated. But you know, that vaunting reputation comes from the sullen watchful army of English teachers and the sinecures of academe who have literary pretensions - either to write fiction themselves or as setters of taste. Most of them went from school to University to a teaching job - they've never been a freelance - so they have a skewed idea about the real world and the fact that writers have to make a living. I gave a talk to a school once and we went for drinks at lunchtime. And I vividly recall the assembled teaching staff blanching when I admitted I'd written a book just for the money. One of them actually said, 'But why did you do that?' She blithely forgot that every month a salary cheque plopped as good as gold through her letterbox. For these people, Amis et al fit the prescription of the Literary Gent."

Hoyle's lack of preciousness about the creative process reflects his route into writing. He grew up in Rochdale and - in his late teens - worked at Turner Brothers, the town's massive asbestos factory. Later, he did "a couple of dead-end office jobs" and - in his early twenties - worked as in actor in rep in Barrow, Bolton and Oldham. He also appeared in TV programmes for Granada, including an early live episode (number six) of Coronation Street. After his stint treading the boards, Hoyle became a copywriter, an occupation that seems to produce creative writers with far more regularity than journalism: think of Peter Carey, Fay Weldon, Salman Rushdie, William Trevor, Scott Fitzgerald, Don DiLillo, Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett…

"When I did the Blake's 7 novels, the motive was the money. I don't do anything else - I write full-time. So I did them quickly and I did them to a high professional standard: when you've been a copywriter for over ten years, you learn to turn your literary hand to pretty well any job that comes along. You have to be very professional, versatile and fast - the deadline for that sort of job is always pretty rapid. You get a brief and if you want to keep the job you write to the brief and you do it on time. You can't say, 'I don't feel like writing today.' You have to feel like it."

There's

a staggering honesty to Trevor Hoyle - and not just in terms of his willingness

to acknowledge the financial imperative behind some of his writing. The

Last Gasp (1983) is a fast-paced science fiction thriller dealing with

eco-politics, evolutionary biology, atmospheric physics, environmental catastrophe

and overpopulation. The book sold well and continues to draw critical praise

for its early embrace of ecological issues. But, for Hoyle, it didn't work.

There's

a staggering honesty to Trevor Hoyle - and not just in terms of his willingness

to acknowledge the financial imperative behind some of his writing. The

Last Gasp (1983) is a fast-paced science fiction thriller dealing with

eco-politics, evolutionary biology, atmospheric physics, environmental catastrophe

and overpopulation. The book sold well and continues to draw critical praise

for its early embrace of ecological issues. But, for Hoyle, it didn't work.

"The Last Gasp was one of the novels I started without having an innate feeling about the shape it should take. It was not only a bugger to write, but was not artistically successful in my terms."

His experience as a copywriter gave Hoyle more than versatility and drive: his first novel The Relatively Constant Copywriter was informed by his experience in a Manchester advertising agency. A complex, non-linear and deeply unsettling exploration of the treacherous terrain of identity, illusion and reality, the Copywriter's dissolute, erotic and violent tale is related in fragmented episodes, a montage of clipped, hardboiled reportage, dense prose-poetry, case histories, shooting scripts and author's notes. Hoyle began work on the book in 1967, but its power to disturb is undiminished: its mercurial experimentation sustains a powerfully coherent story with episodes that resonate long after the final page is turned.

"Like most clichés the one that says every copywriter has a half-written novel in the bottom drawer of their desk turns out to be absolutely true. It was turned down by 18 publishers: the rejection letters said nice things, but ended by saying they didn't want to publish it. I can't remember where I got the money, but I found a printer and published it myself, as Northern Writers in 1972. I was Northern Writers. Self-publishing was much rarer in those days, but the book did OK for me. And after that things started to take off."

By the late 1960s Hoyle teamed up with a couple of friends to set up their own agency. Business was thriving and Hoyle had an Italian suit, a mortgage, a Morris Minor, a wife and two kids. He was not, however, seduced by a future that promised economic security, a bigger house, a bigger car and more expensive holidays.

"Something must have been going on underneath that smooth Italian suit, because I thought 'this is like a honeytrap.' I'd written the Copywriter and published a couple of articles and short stories - and I knew I had to do something drastic because I didn't want to be a copywriter for another 30 years. I knew I'd get used to the money and come to rely on it, so I made an absolutely clean break, sold my share of the business, sold the house and took my family off to Majorca. It seems foolhardy now, but it didn't at the time. The plan was to go out there, write a novel, sell it and carry on existing and working on the basis of that money. The first part of the plan went well, I wrote the novel, The Sexless Spy, but it took another five years to sell it. So we ran out of money in Majorca."

Fortunately for Hoyle, his return to Britain was cushioned by an offer from Granada TV. And from 1973 to 1975, he wrote and presented What's On, a local arts briefing later presented by Tony Wilson.

"Have you seen 24 Hour Party People? " Hoyle asks. "Steve Coogan's impersonation was uncanny. It's worth watching just to see this character who is partly Alan Partridge and partly Tony Wilson."

Hoyle's job with Granada had enormous benefits: first, it paid him a 'handsome wage' and secondly it facilitated the research process for his cult classic, Rule of Night, the story of Kenny Seddon, an alienated, violent teenage skinhead. Hoyle's status as a regular face on regional TV gave him easy access to the pubs and clubs frequented by groups of teenage lads and their girlfriends. Inspired in part by the dehumanising reaction to the arrest of a 'Dale yobbo' (Hoyle is still a season ticket holder at Spotland, Rochdale's home ground), and written 30 years before the current boom in urban hard man literature, Rule of Night has recently been republished by Pomona. A cool, restrained slice of gritty realism, it rejects the allure of 'stylish' violence and the easy moral platitudes of the 1970s to take its readers into Kenny's world and his psyche. He's a hard character to like but, against the odds, we do care what happens to him at the end of the book.

"I

look at Rule of Night today and I'm still very happy with it - it works

on its own terms. Obviously it could have been improved but it's as near as

damn it to what I aimed for. If I had done anything else with it I might have

harmed it.

"I

look at Rule of Night today and I'm still very happy with it - it works

on its own terms. Obviously it could have been improved but it's as near as

damn it to what I aimed for. If I had done anything else with it I might have

harmed it.

"Society is far crueller and harsher than it was in the 1970s. When I look back at that period, it was all localised, Rochdale yobs versus Bury yobs. Now it's bloody random: people going out on a Saturday night in a city run the risk of getting quite violently assaulted. For me, there's a much nastier streak in society. Disaffection has a lot to do with it.

"The other thing disaffection has brought to the fore is the resurgence of far-right organisations in this area. If you look at Burnley, which is not far away, an ordinary former-cotton town like Rochdale, nothing to mark it out, except that sections of the population seem to feel abandoned by Labour, Conservatives and Liberal Democrats and to be turning to the British National Party as an alternative. Oldham, four or five miles from here, has BNP people standing for councillors. A very worrying trend."

A bloody field day

Which brings us to Hoyle's work in progress - a novel dealing with the rise of the far right. The book in tentatively entitled The Kingdom of Darkness, after a quote from Leviathan by the philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679).

"Hobbes was saying 'if we allow things to go on and do nothing, if good men sit by and let evil happen, then we are ushering in The Kingdom of Darkness'. He was talking about Fascism nearly three hundred years before the word was invented. In Germany in the twenties and thirties it was economic deprivation that opened the door, but today it would have to be some other factor - or at least something powerful on top of existing economic conditions. I don't think it too far-fetched that such a thing might happen. How can I put this? I've had a fascination with this neo-fascist bane for around ten years now. So long, in fact, that I'm going to have to get down and write the bloody thing! If you keep thinking about a story without writing it, it evaporates. I'll probably tackle it in the speculative style I used for Vail, with the present shifted vaguely into the future.

"My interest is principally in two things. If you take the Nazi regime I think it's wrong headed for people to deny they had a seductive sexy glamour; actually they had bloody great uniforms, black boots, black uniforms, hats, insignia, skull and crossbones. It's clear that whoever designed them knew what they were about, especially when you compare them to that horrible khaki of the British uniforms. There's a perennial fascination with the trappings of the 1930s and, even now, people think 'bloody hell I could stomp around in one of them'. Never mind the ethos behind it. It's all very well to say the Nazis were awful - of course they were. But we have to try to understand why ordinary people in Germany were so fascinated and attracted by that regime. Why did it have that glamour to it?

"I want the novel to examine both the personal and mass psychology of neo-fascism. It will deal with the fascination people have with this kind of movement - the obvious characteristic is the glamour of the uniforms but there's something deeper - a stronger psychological hook. The book will examine that through various characters. The other thing that interests me is the exploitation of contemporary channels of communication - TV, Internet, text messaging. Could somebody use those to re-introduce fascism, take it out of the ghetto and make it sexy on an international scale again? Think of what Joseph Goebbels did with the technology he had at hand - radio, film reels and newspapers. What could he do with the machinery of instant mass communication? He'd have a bloody field day with the number of channels we have these days - a deluge of propaganda, manipulating millions of people. It doesn't matter what the message is, if you have the means and the money, the message gets across."

This is a theme Hoyle has touched on in earlier books, particularly in Mirrorman (1999), a dizzying but compelling blend of history, science fiction, fantasy and horror. The plot centres on the efforts of a quasi-religious cult, The Messengers of the Fall from Grace, to achieve global domination. So what keeps drawing Hoyle back to the issues of belief and control?

"Religion is still the biggest con game going and it always fascinates me to what bizarre extremes human beings can be pushed in its name: in Mirrorman the Messengers are evil because all religious cults are thus by definition. I get angry with otherwise intelligent people who get taken in by all the claptrap and marketing. For example, the Catholic faith, with all its exotic, guilt-inducing, crazy rituals, could just as easily have been invented by a SF writer - someone, say, as good as Phil K Dick - and The Bible is actually the greatest science fiction novel ever written. I am genuinely baffled when I meet a well-read person, quite sane to all appearances, who turns out to be a Catholic believer. I excuse Graham Greene because I think for him it was a literary device, something to toy with - he wanted his characters to wrestle with something 'big' in life-or-death terms and the Catholic faith was handy. I don't think Greene believed any of that tosh for a minute but he loved the melodrama. Have a look at The End of the Affair to see it set down plain.

"I was recently trying to explain to a Catholic friend that my idea of God or Creator or whatever was best expressed as electromagnetism or electricity. It's a powerful force that pervades the universe but it has no moral sense of right and wrong or good versus evil whatsoever. It simply is. So praying to this particular God is like kneeling in front of a power point and asking a favour. That's how idiotic it is praying to a plaster cast of a virgin or somebody in a thorn crown. My friend wasn't amused."

I ask Hoyle if his strong feelings about religious faith imply a hard-line rationalist take on the human condition.

"No, I have to differentiate here: it's the manmade religions I find objectionable. Human beings are not simply material entities, once you've fed them, once they've had sex, there's the yearning of the human soul, a spiritual concept that can't be located. We need a belief in something bigger than ourselves - numinous things beyond our consciousness, the grandeur of the universe or whatever.

"Fritjof Capra's book The Tao of Physics had a great impact on me with that splicing of quantum physics and Buddhism. Two totally separate disciplines at first sight - a hard science dealing with minute particles and an eastern religion. He makes stunning connections between the two and shows how the same philosophies underpin both concepts. I find that very attractive. I am attracted to Buddhism because it has no God in it - Buddhists have no Supreme Being. These guys are on the right line, no old man with a long grey beard, sitting on a cloud, being worshipped by humanity; no fiery pits, devils with forked tails, a grown up religion in which you can invest some intelligent thought. I'm not a Buddhist, but I am attracted to a philosophy that has more to do with transcendence than social control."

The men in white coats

Quantum physics has been, like totalitarianism and religion, a long-term fixation in Hoyle's work, constituting the major theme of his science fiction series of the late 1970s, the Q trilogy (Seeking the Mythical Future, 1977; Through the Eye of Time, 1977; and The Gods Look Down, 1978). Another is identity, a key focus of Blind Needle, his experimental, existential chase thriller of 1994. Unstable identities, financial shenanigans, murder, social commentary, political satire: all this and - as far as I know - it's the only novel with two concurrently running Chapter Fifteens. So what led Hoyle explore the hazy territory where identity meets personality?

"I didn't sit down to write the book thinking I must address that notion, but it's a concern that leaked into the symbolism of the novel. I hate books that have agendas or set out to prove something. I try to write as honestly as I can and my underlying interests and beliefs seep through by a process of osmosis.

"One of my great heroes in SF is Phillip K Dick, a writer whose life and work addressed that single subject, if you want to narrow it down. What is identity? What does it mean to be human? How can you tell the fake from the authentic? All his books deal with those subjects in one way or another and I am fascinated with them. When I was writing Blind Needle, I was wrestling with various psychological crises and the story was almost certainly driven by the difficult, personal questions I was asking myself.

"The inspiration for the book was a cycling trip I did with my wife in Cumbria which took us through the beautiful countryside of the Lake District and then we wound up in a seaside town which in the book I call Brickton. We were probably there for three hours but the place was so dismal and dreadful, forgotten and thrown on the scrap heap - in direct contrast to the scenery we had just cycled through - that I knew right away I wanted to set something there. Being a fan of film noir I made it into a chase thriller with a fugitive with a dark secret in his past who has conveniently lost his memory. In other words all the staples of the genre but in a contemporary setting."

The

Man Who Travelled on Motorways (1979) is a multi-layered exploration of

fantasy and reality, recollection and illusion, sex and terror and the dynamic

nature of the collective unconscious. Fragmented memories of endless night

drives - bleakly comic and terrifying by turns - highlight the way motorway

travel has impacted on the human psyche. I ask Hoyle if the complex structure

and dense prose style of the book was mediated by the nature of its subject

matter, or if he was trying to attract a specific readership.

The

Man Who Travelled on Motorways (1979) is a multi-layered exploration of

fantasy and reality, recollection and illusion, sex and terror and the dynamic

nature of the collective unconscious. Fragmented memories of endless night

drives - bleakly comic and terrifying by turns - highlight the way motorway

travel has impacted on the human psyche. I ask Hoyle if the complex structure

and dense prose style of the book was mediated by the nature of its subject

matter, or if he was trying to attract a specific readership.

"I never write for an audience, that would be fatal. It is quite a hard book to read. I had to find a style to capture the personality of the book - it is very clotted, not clean and spare like Vail and Rule of Night, but I don't think I could have handled this material with the same approach I took to those books. It wouldn't have worked for me. The approach is dictated by the content: matching the style to the content is the key thing If you get that right then you're 90% there, but if you get it wrong, you end up with a horrible mishmash.

"It was a difficult book to write too: it took three years and I rewrote it two or three times - working on the typewriter in those days. I had to type the damn thing all over again with two fingers. Andy, I know I felt the style was right at the time, but the question as to why I chose that style is a bit of a bastard to tackle after almost thirty years!"

"I don't get too intellectual about what goes into my fiction or examine it too closely for fear that it will place the dead hand of some kind of orthodox or politically correct view over the whole enterprise. I had a very clear idea of what I wanted to say in Vail, but I didn't consciously think about the themes in terms of 'is this character behaving well or badly?' That's not to say there is no moral compass or that all values are arbitrary, just that I set down what feels 'right' and let the character work it out for themselves. I really believe very strongly in gut instinct in creative matters, so it is difficult, if not impossible, to elucidate how certain stuff came to be written and the passion that motivated and informed it. It's my guess that this is the reason many writers resist psychoanalysis - it would tell them too much about their inner workings. It might even, in a sense, 'cure' them of certain neuroses and fixations which actually form the wellspring of whatever it is that makes them writers in the first place.

"I'm simply trying to describe the world as I see it as truthfully and clearly as I can. Of course my interpretation is not the 'right' one - there is no right one - but it will be valid if it is set down honestly. Sometimes I have described a situation, episode or mental process that seems to me to be entirely realistic, if not naturalistic. I've not invented it - just transcribing what I see and feel - only to find that readers find the scene or the emotion to be spinning off into the wildly surreal. I don't think so; it's just how I happen to see the world. But don't tell the men in white coats."

Interview from Internet.

Trevor Hoyle, most noted for his works of science fiction, is author of speculative novels, such as Vail, The Last Gasp, and The Man Who Travelled on Motorways. In the late 1970s he gained recognition for his "Q" series, featuring Christian Queghan, a scientific investigator possessing the ability to journey through time as well as to hypothetical worlds.

Seeking the Mythical Future depicts Queghan placed into a parallel universe where humans and dinosaurs are contemporaries and where those unwilling to conform to rigidly policed thoughts and beliefs are thrown into Psychological Concentration Camps.

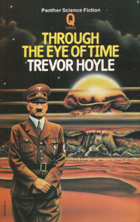

In

Through the Eye of Time, a group of scientists attempting to duplicate

the human brain have chosen that of Adolf Hitler as their prototype. Investigating

the research, Queghan unveils an alternate universe in which Germany (as opposed

to the United States) developed the first atomic bomb. Queghan's quest becomes

to enter this other reality in an attempt to avert the threat it poses to

the known reality.

In

Through the Eye of Time, a group of scientists attempting to duplicate

the human brain have chosen that of Adolf Hitler as their prototype. Investigating

the research, Queghan unveils an alternate universe in which Germany (as opposed

to the United States) developed the first atomic bomb. Queghan's quest becomes

to enter this other reality in an attempt to avert the threat it poses to

the known reality.

The third volume, The Gods Look Down, tells of Queghan working with another scientist on decoding texts from ancient history. Upon realizing that his colleague is seeking to alter history using the results of the research, Queghan draws upon his ability to pass into alternate realities in an attempt to stop him.

Vail is a black comedy set in a dreary, futuristic Britain. The work tells of how the title character loses both his wife and daughter in a highway accident and later arrives in London, where he is drawn into a sinister, scheming world. Populated by the off-beat, the bizarre, and the morally corrupt, the city defies conventional urban activity. While Vail seeks to sustain his belief in a larger order of things through much of the work, he is ultimately engulfed by the growing anarchy surrounding him. British Book News contributor Martin Seymour-Smith found Vail reminiscent of anti-utopian works such as George Orwell's novel 1984, the motion picture A Clockwork Orange by Stanley Kubrick, and, most of all, the novel We, a critique of the former Soviet Union by Yevgeny Ivanovich Zamyatin. "The popular reflexes of blitz patriotism and cheque-book journalists' voyeurism jump off the page," commented Times Literary Supplement contributor Neville Shack, concluding that "the extremism of all this serves a comedy which is even blacker than ... diesel."

In The Last Gasp, British marine biologist Gavin Chase uncovers a potential global disaster in which the world is being drained of its oxygen supply as forests and oceanic microscopic plant life, the main suppliers of the planet's oxygen, dwindle away. When Chase and two other scientists attempt to notify the government and scientific community, they stumble upon a secret Russian-American plan to launch an "environmental war" in which three quarters of the earth's population would be exterminated in order to provide oxygen for the remaining population. Comparing Hoyle's writing to that of Aldous Huxley, Washington Post reviewer Carol Van Strum commented that, "The Last Gasp reads more like a documentary thriller than science fiction." She also noted that it was a "landmark in the emerging field of eco-fiction."

In The Man Who Travelled on Motorways, the narrator, a literary anti-hero, falls victim to a series of psychoses while driving through the commonplace landscapes of Manchester, London, and South Lancashire, in England. His condition generates memory distortion and triggers vivid fantasies. The novel also incorporates sex scenes, in which the narrator exploits women to satisfy his personal needs, and elements of science fiction, such as a character described in the book as residing in "a different spacetime continuum." Terming the work "an experimental 'mainstream' novel," Science Fiction & Fantasy Book Review contributor Richard Mathews found it to be "strongly written, cautiously experimental, with an impressive characterization of the narrator."

Hoyle told CA: "Much of my full-length fiction has been concerned with `speculative' subjects, such as the precarious ecology of the planet and its eventual, possible demise due to mankind's greed and short-sightedness (eg: The Last Gasp)."